Can Being Different Make You a Target?

Middle school is hard for everyone. But what happens when you're trying to navigate those difficult years while also being on the autism spectrum?

For me, it meant being unable to read the social cues that came naturally to others. It meant being desperate to fit in but not understanding how. And it meant becoming a target.

My experience at Forest Ridge Middle School taught me lessons the hard way—through manipulation, bullying, and well-meaning adults who didn't actually help. I'm sharing parts of my story here because I believe it can help other young people on the spectrum, as well as the parents and educators who support them.

This is about what happens when you're different in a place that demands conformity. But it's also about resilience, self-advocacy, and the wisdom that comes from survival.

Table of Contents

The Warning Signs of Fake Friendship

Why Monitored Socialization Doesn't Work

When Adults Scapegoat the Autistic Student

Understanding Stimming in Hostile Environments

Fighting Back Against Rumors and Bullying

Key Takeaways for Parents and Educators

Moving Forward

The Warning Signs of Fake Friendship

By the end of sixth grade, I was allowed to invite classmates to lunch in the resource room under strict conditions. Only girls could come, I couldn't invite certain people, and adults had to extend the invitations for me.

Suddenly, three girls from the "in crowd" became very friendly. They called me regularly, came to my Super Bowl party, and seemed genuinely interested in being my friend. I was thrilled.

The reality was different. I was being used as a messenger between them. Phone conversations consisted of "What did she say about me?" and "Did she mention anything about our argument?" I didn't understand this at the time because people on the autism spectrum often miss subtle social cues like hidden agendas and manipulative patterns.

What Fake Friendship Looks Like

When the girls came to my Super Bowl party, they ran through my house like it was a museum tour. They were interested in seeing where I lived, not in spending time with me. My mom noticed immediately. The invitations were never reciprocated.

Here are the warning signs I learned to recognize:

Questions that extract information about others - "What did she say about me?" is a classic red flag that someone is using you as a go-between.

Sudden interest after previous indifference - When people who ignored you suddenly become friendly, there's usually a reason. They want something.

One-sided invitations - If you're always the one hosting or inviting, and they never reciprocate, that's a clear sign the friendship isn't genuine.

Interest in your stuff over you - People who spend time exploring your house or asking about your things rather than engaging with you are treating you like a museum exhibit.

Different behavior depending on audience - Friends who act one way around adults and another way around peers aren't being genuine.

Learning to spot these patterns early can save you from months or years of being used. In my book, I explore these dynamics in much greater depth and provide strategies for protecting yourself from social manipulation before it escalates.

Why Monitored Socialization Doesn't Work

When classmates did join me for lunch, every word was monitored to ensure I didn't say "anything inappropriate." The adults thought they were helping me learn social skills.

They weren't.

One day, I asked a lunch companion questions about her dating history. She answered politely. The conversation seemed fine. Only after lunch did staff tell me I'd been "nosy."

The Problem with After-the-Fact Correction

Post-hoc correction doesn't teach social skills. It teaches fear of making mistakes. I walked away from that interaction not knowing what questions were appropriate, only that I'd done something wrong.

What would have actually helped:

Pre-teaching conversation strategies - Before lunch, give specific prompts or topics to practice. "Today, try asking about weekend plans and hobbies."

Real-time gentle redirection - If a conversation goes off track, redirect in the moment with a soft "Let's shift to talking about..." rather than lecturing afterward.

Specific skill practice - Assign one conversation skill to focus on for a week. Practice it daily, get feedback, master it, then move to the next skill.

Constructive examples - Show what good conversation looks like, not just what bad conversation looks like.

Surveillance followed by criticism creates anxiety. Structured practice with immediate feedback builds competence.

When Adults Scapegoat the Autistic Student

Seventh grade brought more freedom, but also more opportunities for things to go wrong. In math class with Ms. Morgan, a classmate named Emilie would constantly bug me to make silly faces or gestures when the teacher's back was turned.

I'd eventually give in just to get her to stop asking. Wrong approach, I know now.

Here's where things got absurd: Emilie had a very distinctive laugh. Ms. Morgan learned to automatically kick me out of class whenever she heard that laugh, without even looking to see what happened.

It was pure classical conditioning. Emilie's laugh became the signal for my removal from class.

The Assistant Principal Meeting

This pattern continued until I was sent to the assistant principal's office twice. The second time, Ms. Anderson, my special education teacher, tried to explain what was actually happening in math class.

The assistant principal, Mr. Benson, cut her off.

"If you can't behave properly in that class, I am going to call your father and have him take you home for five days. Is that clear?!" he yelled at me.

Ms. Anderson tried again to explain. He told her he didn't care to hear it.

This is textbook scapegoating. The autistic student becomes "the problem" even when adults know there's more to the story. Students learn quickly that reporting me to staff is an effective weapon. They had visual proof of my "otherness" through seeing me escorted separately, which reinforced that I was different, lesser, fair game for manipulation.

What Should Have Happened

The assistant principal should have:

Listened to the full context from Ms. Anderson

Investigated the classroom dynamics

Addressed the student who was prompting the behavior

Worked with the teacher to change the seating arrangement

Provided me with strategies to decline requests from peers

Instead, I learned that the system would always blame me first and ask questions never.

For parents and educators dealing with similar situations, my book provides detailed strategies for ensuring autistic students aren't automatically scapegoated when behavioral issues arise in the classroom.

Understanding Stimming in Hostile Environments

In science class, I was paired with a classmate named Misty for group work. She looked physically ill at the prospect of working with me.

I was rocking back and forth, which is called stimming. It's a self-soothing behavior that helps many autistic people manage stress and anxiety.

What Stimming Is

Stimming (self-stimulatory behavior) is a core feature of autism that includes:

Hand flapping

Rocking

Spinning

Finger flicking

Pacing

Humming

Repeating words or phrases

Using objects repetitively

For me, rocking was calming. The back-and-forth motion reminded me of my grandparents' rocking chair, one of my few peaceful childhood memories. In that hostile classroom environment, it helped me cope.

When Self-Soothing Becomes Ammunition

Other students didn't understand stimming. They saw another thing to mock.

Classmates started imitating my rocking. One student encouraged others to join in. I got defensive and told them to stop. Then I saw Misty mocking me too, making exaggerated faces and repeating "Stop" in a mocking tone.

I was stunned that she would participate in the bullying.

The teacher did nothing to intervene effectively. The laughter continued. My self-soothing behavior became entertainment for others.

What I Needed Instead

Ideally, the classroom environment should have been one where stimming was understood and accepted. The teacher should have:

Educated the class about neurodiversity and different ways people self-regulate

Immediately shut down mocking behavior

Separated me from students who were bullying

Provided me with additional coping strategies

While stimming is a neurological need that shouldn't have to be hidden, having additional tools would have helped me navigate that hostile environment better. I share these alternative strategies in detail in my book because they're crucial for autistic students in mainstream classrooms.

Fighting Back Against Rumors and Bullying

During a swimming unit in gym class, someone asked me to move out of the way in the locker room while I was changing. I wasn't as skilled as other girls at covering myself while changing positions.

Somehow, this became a rumor that spread through all three grades: "Sonia walks around the locker room naked."

The Relentless Harassment

The comments came from everywhere:

"I heard you were walking around naked in the locker room. Are you a lesbian?"

"Why would you do that? You're a seventh grader—you should know better."

"Locker rooms are for changing clothes, not for walking around naked."

Every comment was accompanied by laughter from bystanders. One day in gym class, a classmate screamed loud enough for everyone to hear: "Maybe we can get someone to walk around naked in the locker room like Sonia."

I stood up for myself. "I didn't do that."

"It's true. Ask anybody in here," she shot back.

Silence from the other girls. Then, as people lined up to leave: "It's not a rumor; it's true."

I ended up in tears, escorted out of reading class to the resource room.

Being Persistent When Adults Don't Want to Help

I brought my concern to Mrs. Horowitz, the guidance counselor. The first time, she told me to stop crying about the rumor. She was dismissive and acting lazy about the situation.

It took me being persistent before she finally took action. I knew if nothing changed, the harassment would only get worse.

Mrs. Horowitz eventually called several classmates to her office and discovered that Donna had started the rumor. Donna admitted she saw me standing undressed while moving to a different spot because someone asked me to move. She didn't know why I did it, but she started the rumor anyway.

The Disappointing Outcome

Mrs. Horowitz's solution was minimal:

Tell Donna she wouldn't call her mother

Have Donna tell people who bring up the rumor that it isn't true

Teach me how other girls cover themselves while changing

That was it. A slap on the wrist for Donna. More "skills training" for me. No real consequences for spreading a harmful rumor that led to weeks of harassment.

What I'm Proud Of

Even though the outcome was disappointing, I was proud of myself for being persistent. I didn't give up when the adult initially dismissed my concerns. I kept pushing until she took action.

That persistence came from an inner strength I didn't know I had. Despite all the challenges I faced, both from peers and from adults who should have helped me, I had the drive not to give up.

This is a lesson I want other autistic students to learn: Your voice matters. Your concerns are valid. If one adult won't help, find another. Keep advocating for yourself until someone listens.

Key Takeaways for Parents and Educators

Recognize Social Manipulation Early

Autistic students are vulnerable to social manipulation because they often miss subtle cues. Watch for warning signs like:

Sudden friendship from previously disinterested peers

Questions that extract information about others

One-sided relationships where your child always gives but never receives

Different behavior from "friends" depending on who's watching

Teach Social Skills Proactively

Don't wait until mistakes happen to correct them. Pre-teach strategies before social situations:

Give specific conversation prompts to practice

Role-play different scenarios

Provide real-time gentle redirection

Focus on one skill at a time until mastered

Get the Full Story Before Disciplining

When behavioral issues arise, investigate thoroughly:

Listen to the special education staff who know the full context

Ask about peer dynamics and who might be prompting behaviors

Consider whether the autistic student is reacting to or being manipulated by others

Apply consequences fairly to all students involved, not just the autistic student

Understand and Accept Stimming

Self-stimulatory behaviors are neurological needs, not misbehavior:

Educate classrooms about neurodiversity

Create environments where stimming is accepted

Immediately shut down mocking of stimming behaviors

Provide additional coping strategies when needed

Take Bullying Reports Seriously

When an autistic student reports bullying:

Act immediately, don't dismiss their concerns

Investigate thoroughly to identify who started rumors or harassment

Apply meaningful consequences to students who bully

Follow up to ensure the bullying has stopped

Advocate for Real Solutions

If you're a parent:

Request written evaluations when you have concerns

Ask for measurable goals in IEPs

Ensure evidence-based methods are being used

Communicate regularly with all adults supporting your child

Don't accept dismissive responses from school staff

If you're an educator:

Coordinate with other teachers and specialists supporting the student

Share information about what's working and what isn't

Don't automatically blame the autistic student when problems arise

Create inclusive classroom environments where differences are respected

Moving Forward

My middle school experiences were difficult, but they taught me invaluable lessons about self-advocacy, resilience, and what actually helps autistic students succeed in mainstream education.

The system failed me in many ways. Adults who should have protected me often made things worse. Peers who should have been taught empathy were allowed to bully without real consequences. Restrictions that were supposed to help me only isolated me further.

But I survived. I learned. And now I'm sharing what I know so others don't have to learn these lessons the hard way.

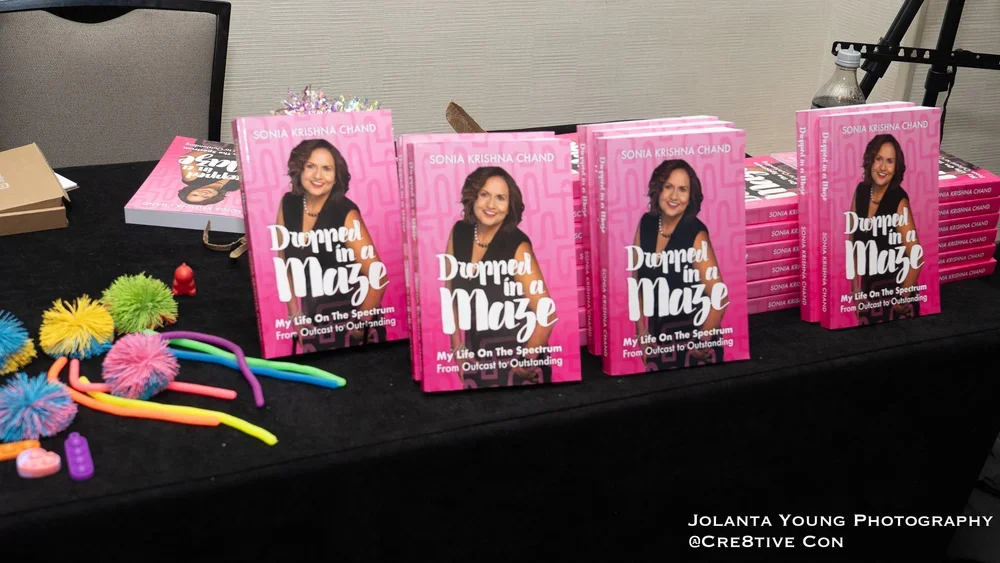

If you want the complete story of my middle school experiences, including many more incidents I couldn't fit into this blog post and the detailed strategies I wish someone had taught me back then, my book provides everything you need. It's written for autistic students who are struggling, parents trying to support their children, and educators who want to do better.

Order for yours here