My Summer of Loneliness and Self-Discovery

There's a moment in every struggling person's life when reality hits differently. For me, it happened during the summer of 1996, between seventh and eighth grade. After years of desperately trying to make friends, throwing birthday parties that felt more like performances than celebrations, and bending over backward to fit in, the truth finally crashed down on me like a tidal wave.

Nobody was coming. Nobody wanted to hang out. Every invitation was met with "I can't." And this time, I couldn't ignore it anymore.

That summer taught me brutal lessons about fake friendships, self-hatred, and what happens when you internalize every cruel message thrown your way. But it also planted seeds of self-advocacy and showed me what real friendship could look like—even if I wasn't ready to receive it yet.

If you've ever felt friendless, if you've ever wondered why people keep rejecting you, or if you're watching your autistic child struggle with similar pain, this story will resonate deeply. More importantly, the lessons I learned might help you avoid some of the mistakes I made.

Table of Contents

Teachers Saw the Problem But Did Nothing

The Phone Call That Confirmed My Fears

When I Finally Told the Truth

Meeting Real Friends Outside of School

How I Became Toxic to the One Person Who Cared

The Internal Battle That Destroyed My Friendship

Key Takeaways for Parents and Teens

Moving Forward

Teachers Saw the Problem But Did Nothing

At my annual end-of-year case conference meeting, teachers didn't hold back in their reports. They described my social skills as "below average" and noted my peculiar behaviors. My Social Science teacher wrote that "Sonia tries too hard to get people to like her." My reading teacher even documented how I was "the target of cruel jokes and peer ridicule in the hallways."

Everything was there in black and white. The teachers saw what was happening to me.

But here's what didn't happen at that meeting: no discussion about next steps. No plan for how to help me improve my social skills as part of my Individual Educational Plan (IEP). The school administrator just read through the reports like they were reading a magazine article, then moved on.

The only decision made? Take me completely off restrictions for eighth grade. At the time, I didn't care one way or another.

What Parents Need to Know

If teachers are commenting on your child's poor social skills at case conference meetings, this is your moment to speak up. Don't let the meeting end without answers to these questions:

What specific interventions will address the social skills issues?

Who will be responsible for teaching these skills?

How will progress be measured?

What support will be provided to prevent bullying?

How often will we reassess and adjust the plan?

Being proactive at these meetings can change the trajectory of your child's school experience. I wish my parents had known to push for more than just reading reports out loud.

The Phone Call That Confirmed My Fears

During that lonely summer, I spent my days trying to connect with classmates who clearly didn't want to connect with me. Every invitation was met with "I can't" or vague excuses. But I kept trying because I didn't know what else to do.

One evening, I was on the phone with a classmate named Eileen. What she said next would stick with me for years.

"Sonia, you should know a lot of people hate you."

This wasn't news. I'd been told multiple times by various people, including Misty, that "a lot of people make fun of you." But hearing it stated so bluntly still hurt.

"I am not a weirdo," I protested.

"Yes, you are! I heard about things you used to do in sixth grade, even. I heard about all your crying outbursts. I also heard about those cheers. That was all really stupid. You are weird!"

"Who hates me?" I asked.

"I better not tell you because you will cry forever."

"Okay, I guess I am hated then," I said, my voice flat.

"Yep!"

I hung up the phone.

The Social Cues I Missed

Looking back, Eileen was giving me an important social cue: give up on trying to be her friend or anyone else's friend from that group. When she said "a lot of people hate me because I'm annoying and weird," she was really saying "I don't really like you either."

But I didn't catch it at the time. That's the challenge with autism—reading between the lines doesn't come naturally. We take words at face value and miss the hidden messages underneath.

Eileen had always played both sides. She'd laugh with others who set me up and participate in mocking me in gym class, then turn around and tell me how "disruptive" I was with her friends. She was never my friend. She was documenting my failures for entertainment.

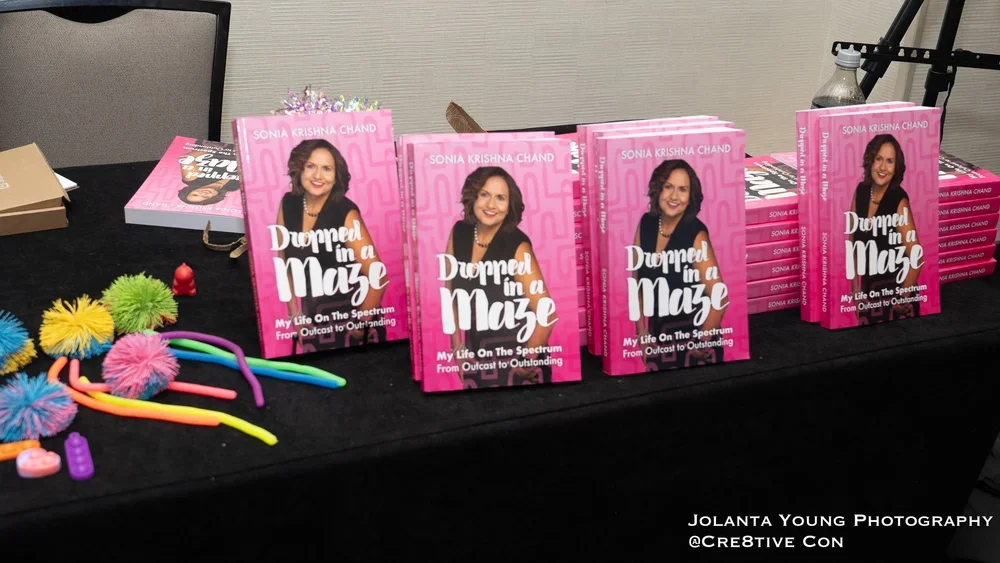

In my book, I explore the full dynamics of these toxic relationships and provide strategies for recognizing when someone is playing both sides before you invest emotional energy in them.

When I Finally Told the Truth

My parents took me to see a new psychiatrist that summer at a major teaching hospital in Chicago. I was hesitant because of my previous bad experience with Dr. Patel, but my mom insisted. They automatically thought Dr. Wagner was good because of his position at an acclaimed hospital.

I would learn that just because someone works at a prestigious institution doesn't mean they're a good fit for you as a patient.

Dr. Wagner got a history of everything that had happened and sold me on one thing: "Let's work on getting you some friends." I was desperate enough to believe him.

On the drive to the hospital, my parents asked if I was planning on throwing a birthday party that year.

For the first time, I was honest with them.

"No," I said. "Nobody will come, at least not for the right reasons."

"Why don't you think they will come?"

"Because they have been blowing me off this whole time. We are into August now. Nobody wants to hang out with me. People keep telling me, 'I can't, I can't, I can't.' There's simply no need for a birthday party."

This was the first time I had been vulnerable and outspoken with my parents. For a brief moment, I felt brave. I was proud of myself for telling the truth instead of pretending everything was fine.

My dad tried to push me to make friends with his colleague's daughters—the same girls I didn't get along with at Indian cultural events. I told him no. It wasn't easy for my family to understand why I was having social issues, and it would remain that way for a long time.

Meeting Real Friends Outside of School

Outside of school, my family was part of an Indian cultural group made up of down-to-earth families from neighboring townships and suburbs. Some we already knew, but there were new families too.

I connected most with Meera. She was a year older than me and lived in the neighboring township of Oakland. Meera was quite mature for a 14-year-old and carried herself differently than most teenagers.

While other kids were interested in bonding with their age groups, Meera preferred helping the aunties (what Indian people call elderly women) in the kitchen. But when she hung out with the rest of us, she was fun, kind, and had an open vibe about her.

Our friendship started slowly after we performed a skit together for a Diwali show in October 1995.

Meeting Ambika

I also met Ambika through the cultural group. She was a year younger than me and lived in Dyers Village. Ambika had a youthful glow and a bubbly personality. One of my favorite memories was her trying to sing along to popular pop songs but not knowing the lyrics and just making up her own. We'd all laugh—the good kind of laughter, the kind that includes everyone.

When Ambika had a birthday party and invited Meera and me, I noticed something important. Even though the girls were pranking cute guys in their grade, they weren't making prank calls the way people did at my house. The difference was clear: people were laughing with Ambika and making sure she was included. They didn't just help themselves to the phone or her things.

I could see a stark difference in energy between Ambika's friends from Dyers Village and people from Forest Ridge. Dyers Village was a bigger, more diverse township without the elitist attitude that Forest Ridge pushed. There was a more relaxed energy because the pressure to maintain status simply wasn't there.

During the party, I noticed Meera wasn't really connecting with many of the girls. She and I sat on the couch in Ambika's basement and chatted. This is where I learned about her strong interest in dancing and tennis. Our love for dancing and music connected us.

Sadly, Ambika's family moved to India for her father's sabbatical at the beginning of summer 1996. I felt sad to see them go and missed them dearly.

How I Became Toxic to the One Person Who Cared

As my friendship with Meera grew towards the end of seventh grade and into the summer, I should have been grateful. Someone actually wanted to spend time with me. Someone saw value in our friendship.

But I couldn't see it. I couldn't appreciate it. Because I had become toxic.

Let me be clear about something: I was the problem. I hated myself and turned all the negative messages from others inward so that I would hate me too. This is what made me toxic.

I didn't realize how negative I had become until moments came up over the summer when I would start berating myself in front of Meera.

When I say "berate myself," I mean I would say the meanest things about myself to myself:

"You're trash"

"You're junk"

"You're unworthy"

"You're stupid"

"You're scum"

I was desperate to feel cared about and accepted. I wanted someone to prove me wrong about all these terrible things I believed about myself.

What I Was Really Looking For

The only way I felt I could be proven wrong was if people from my school came around and said, "Sonia is cool and worthy of being around. She didn't deserve all that bullying. We're sorry you went through that."

I was looking for answers to the big questions:

Why was it okay to always target me?

What was in it for everyone to laugh at me and not like me?

What made me so different that I deserved this treatment?

What I didn't realize then was this was an internal job. It was my responsibility to validate myself. This is where attending therapy sessions and supportive group therapy—where social, emotional, self-esteem-building, and communication skills are taught—would have made all the difference.

In my book, I detail the therapeutic approaches that eventually helped me build self-worth from the inside out, rather than seeking it from people who would never give it to me.

The Internal Battle That Destroyed My Friendship

There were times I cried to my mom and even to Meera about all the bullying and how I was friendless at school. There were also times when I had fun with Meera. I learned Indian dance moves, we watched movies together, and we played tennis.

Despite the validation Meera tried to give me—letting me know I wasn't trash—I was dying inside. I was depressed and anxious about having to go back to the same place where I had been broken down so badly. The place where I was left friendless and lonely.

The Physical Toll of Emotional Pain

I started to feel the pain in my body. My stomach hurt every day. I knew it was due to emotional pain rather than any physical ailment—even back then, my intuition told me that.

The constant self-deprecating dialogue played on repeat all day long:

"You are trash. Nobody likes you. You were and are never invited by people at school to anything. Everybody thinks you're a baby and a weirdo. Nobody really likes you, and nobody will ever be your friend."

This internal soundtrack certainly didn't help my stomach pain or my ability to be present with the one person who actually cared about me.

Missing What Was Right in Front of Me

I couldn't appreciate the good times as much as I should have. If I could rewind time, I would've appreciated all the moments I had with Meera instead of constantly getting down on myself.

I would've taken notice of the fact that someone was actually trying to be my friend.

But all I could focus on was everything that happened during school—all the alienation, ostracism, and bullying. It was all I could talk about. It was all I could perseverate on.

Meera, understandably, grew tired of it.

When the Friendship Ended

Meera and I remained close for a little bit at the beginning of eighth grade. She eventually distanced herself from me.

I remember trying to discuss with her how I noticed we weren't hanging out on weekends like we used to. All she said was, "You have to understand my situation. I am busy with school."

I respected her decision. I would see her sporadically at cultural group meetings after that. Meera already had plenty of other friends from her school by then.

What made the friendship break even more saddening was that Meera was my only friend. Now that was gone, and it was my fault.

Making Amends Years Later

I wrote to her years later apologizing for my behavior. She was very sweet about the letter and denied that I had anything to do with the friendship breaking—a generous lie on her behalf.

I knew what I had done. Even though I regret the way I treated Meera at the time, I have learned to have compassion for myself and forgive myself for not knowing any better back then.

I look back now and feel ashamed of how I handled that friendship. But I also understand that I was a deeply hurt child who didn't have the tools to process trauma while simultaneously maintaining a healthy friendship.

The full story of this friendship—and the specific therapeutic interventions that could have helped me handle it better—is something I explore in depth in my book. These lessons are crucial for any teen or parent navigating similar struggles.

Key Takeaways for Parents and Teens

For Teens Who Are Struggling

Someone showing you friendship is precious—don't take it for granted. Even if you've been going through a tough time being bullied, if someone shows you genuine friendship, try to relish the moment. Friendships thrive when both people are happy and can do fun things together. Friendships don't thrive when one person is always negative and talking about their issues.

Bullies want you to internalize their messages. Bullies want you to feel bad about yourself as part of their scheme to exert power and control over you. Please remember that the messages they give you are lies designed to make you feel bad. They are not the truth about who you are.

Self-validation is an inside job. You cannot wait for the people who hurt you to validate you. They won't. Your healing and self-worth must come from within, supported by people who genuinely care about you—not from the approval of people who have shown you they don't value you.

Negative self-talk becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. When you constantly berate yourself, you push away the people who actually want to be your friend. They can't compete with the negative voice in your head, and they'll eventually grow tired of trying.

For Parents of Struggling Teens

Case conference meetings require active participation. When teachers document social skills issues, bullying, or peer ridicule, demand concrete action plans. Don't let the meeting end with just reports being read aloud. Push for specific interventions, timelines, and measurable goals.

Prestigious doesn't mean appropriate. Just because a professional works at a well-known institution doesn't mean they're the right fit for your child. Trust your instincts and your child's feedback about whether a therapist or doctor is actually helping.

Watch for signs of internalized negativity. When your child starts making extremely negative comments about themselves, they need immediate mental health support. This isn't typical teenage angst—it's a sign they've internalized bullying messages and are in real distress.

Create opportunities outside of school. Cultural groups, hobby-based activities, and community organizations can provide friendships with peers who don't know your child's "reputation" at school. These fresh starts are invaluable.

Therapeutic support should include specific skills. Look for therapy that teaches social skills, emotional regulation, self-esteem building, and communication strategies—not just talk therapy that processes feelings without building new capabilities.

Moving Forward

The lessons from that summer didn't fully crystallize until years later, after I'd done the therapeutic work I needed. But looking back now, I can see how that painful period was a turning point—even if I couldn't appreciate it at the time.

If you're going through something similar, whether as a struggling teen or as a parent watching your child suffer, know that there is a path forward. The strategies I eventually learned—and wish I'd known during that summer—are detailed in my book, along with the complete story of how I moved from self-hatred to self-acceptance.