6 Hard Truths About Social Expectations When You're Autistic

You spent weeks planning it. You invited people who seemed interested. You built up this vision in your head of how it would all unfold—the perfect celebration that would finally prove you belonged, that you had friends, that you were just like everyone else.

Then reality hits. One by one, people cancel. The plans fall apart. You end up alone on what was supposed to be your big night, eating fast food by yourself while everyone else celebrates with their tight-knit friend groups.

For autistic people who struggle with social connections, this pattern is painfully familiar. We hear about how others celebrate milestones and assume we can create the same experience. We mistake polite responses for genuine commitment. We build elaborate fantasies to cope with loneliness, then crash when reality refuses to cooperate.

This is about the hard lessons I learned when my 21st birthday became one of the most humiliating experiences of my college years—and what every autistic person needs to understand about the difference between acquaintances and actual friends.

Table of Contents

Truth #1: Acquaintances Are Not Friends (No Matter How Nice They Seem)

Truth #2: "Common Courtesy" Responses Don't Mean Commitment

Truth #3: Your Fantasy Fills the Gap Where Real Friendships Should Be

Truth #4: You Can't Build a Celebration on Casual Connections

Truth #5: Oversharing With the Wrong People Damages Your Reputation

Truth #6: Desperation Pushes People Away Instead of Drawing Them In

What Actually Builds Real Friendships

Key Takeaways for Managing Expectations

Truth #1: Acquaintances Are Not Friends (No Matter How Nice They Seem)

The Fundamental Mistake

When I planned my 21st birthday celebration, I invited people I barely knew. I had:

Taken one class with Savannah over the summer

Watched TV a handful of times with Tia

Seen various floormates occasionally in the dorm

These were acquaintances at best. But because I was desperate for friends and they'd been polite to me, I convinced myself they were close enough to celebrate my birthday.

Understanding the Difference

Acquaintances:

People you see regularly in shared spaces

Classmates you chat with before or after class

Neighbors you exchange pleasantries with

Colleagues you make small talk with

Friends:

People who actively seek out your company

Individuals you've spent significant one-on-one time with

Those who share personal information reciprocally

People who reach out to you, not just respond when you reach out

Why Autistic People Confuse the Two

Autistic people often struggle to distinguish acquaintances from friends because:

Limited social experience means we lack the pattern recognition that helps neurotypical people gauge relationship depth.

Literal thinking makes us take polite responses at face value rather than reading between the lines.

Desperate for connection causes us to elevate any positive interaction into potential friendship.

Difficulty reading social cues prevents us from noticing when someone is being polite versus genuinely interested.

The Reality Check

Most of the people I invited weren't spending time with me outside of class or casual dorm encounters. They hadn't invited me to their events. They didn't text or call me to hang out.

These weren't friends. They were people who knew my name and were polite when they saw me.

Expecting them to celebrate my birthday was asking for a level of emotional investment they'd never demonstrated.

Truth #2: "Common Courtesy" Responses Don't Mean Commitment

What People Actually Mean

When I told people about my birthday plans over the summer, many said things like:

"That sounds fun!"

"I'd be up for that"

"Yeah, maybe I'll come"

"We'll see what happens"

I took these responses as commitments. They were actually polite ways of saying "maybe" or even "probably not."

The Polite Response Trap

Neurotypical people use vague, noncommittal language as social lubrication. When they say "I'd be up for celebrating," they often mean:

"That's a nice idea but I'm not committing"

"I'll come if I don't have anything better to do"

"I'm being polite but don't actually plan to attend"

"I'm leaving myself an easy out"

What Actual Commitment Sounds Like

Compare those vague responses to what actual commitment looks like:

"Yes, I'll be there! What time should I meet you?"

"I'm definitely coming. Should I invite anyone else?"

"I've marked it on my calendar. Looking forward to it!"

"I'll make sure I'm free that night"

Notice the difference? Real commitment is specific, enthusiastic, and action-oriented.

Why This Matters for Autistic People

Autistic people tend to communicate directly and honestly. When we say we'll do something, we mean it. We assume others operate the same way.

This creates painful misunderstandings when we take polite, non-committal responses as genuine promises.

Truth #3: Your Fantasy Fills the Gap Where Real Friendships Should Be

Building the Story in Your Head

Throughout the summer, I constructed an elaborate vision of my 21st birthday:

Group dinner at the Italian restaurant downtown

Everyone going to bars together afterward

Celebrating with friends who cared about me

Finally feeling like I "arrived" and belonged

This fantasy became more real to me than actual reality. I replayed it in my mind constantly, adding details, imagining conversations, picturing the whole evening.

Why We Build Fantasies

Fantasy serves important psychological functions when you're lonely:

It provides hope that things will eventually get better and you'll find your people.

It creates temporary relief from the pain of current isolation.

It offers control over an imagined scenario when real relationships feel impossible to build.

It fills the void where genuine connections should exist.

The Danger of Living in Fantasy

The problem with elaborate fantasies is they:

Set unrealistic expectations that reality can't possibly meet.

Prevent you from seeing the actual state of your relationships clearly.

Increase devastation when the fantasy inevitably crumbles.

Distract from building real connections by providing imaginary ones.

The Crash

When the fantasy bubble burst—when people canceled one after another, when Tia said "I'll only come if I feel like it," when Nadia had to work—the emotional crash was severe.

I cried every day the week of my birthday. The anxiety built to the point where I could barely eat. The cortisol in my stomach made me physically ill.

The gap between fantasy and reality was so extreme that it felt like trauma.

Truth #4: You Can't Build a Celebration on Casual Connections

The Foundation Problem

Imagine trying to build a house on sand. No matter how well you design it, the foundation won't support the structure. The same applies to celebrations built on casual acquaintanceships.

What I Did Wrong

I made several critical errors:

I invited people I barely knew to an intimate celebration that requires close friendships.

I assumed their politeness meant closeness when it just meant they had good manners.

I didn't have established patterns of hanging out with these people outside structured activities.

I expected them to prioritize my event when they had no emotional investment in me.

What Milestones Actually Require

Celebrating major milestones like 21st birthdays requires:

Close friends who genuinely care about you

Established relationships with regular contact and reciprocal investment

People who seek you out, not just respond when you reach out

Mutual emotional investment built over time through shared experiences

You can't manufacture this foundation in a few weeks or months of casual contact.

The Alternative Approach

Instead of planning an elaborate celebration with acquaintances, I could have:

Celebrated with family who genuinely cared

Done something meaningful alone or with one close person

Acknowledged I didn't yet have the friend group for the celebration I wanted

Set a goal to build those friendships before the next milestone

This would have been emotionally difficult but far less devastating than watching an elaborate fantasy crumble.

Truth #5: Oversharing With the Wrong People Damages Your Reputation

What I Shared (That I Shouldn't Have)

According to my floormate Ankita, I had damaged my reputation by sharing personal information with people who weren't close friends:

Talking about having a crush on someone who didn't like me back

Mentioning I'd never been kissed

Sharing personal struggles with people I barely knew

Why This Matters

Information you share gets used in ways you can't control:

It becomes gossip that spreads through social networks.

It gives people ammunition to mock or judge you.

It makes others uncomfortable when shared prematurely in relationships.

It signals poor social boundaries, which makes people wary of getting closer.

The Oversharing Trap for Autistic People

Autistic people often overshare because:

We struggle to gauge relationship depth and don't know what's appropriate to share at different stages.

We're honest and straightforward by nature and assume others will be too.

We're desperate to connect and use personal disclosure to create intimacy quickly.

We don't realize information spreads and gets used against us.

What Appropriate Sharing Looks Like

Information should be shared gradually as relationships deepen:

Early stage (acquaintances):

Surface-level topics: classes, weather, general interests

Safe small talk that doesn't reveal vulnerabilities

Developing friendship:

Some personal preferences and opinions

Stories about experiences that don't involve deep emotions

Interests and hobbies in more detail

Close friendship:

Personal struggles and challenges

Romantic interests and rejections

Deeper emotional experiences

Vulnerabilities and insecurities

Sharing deep personal information with acquaintances creates discomfort and damages how people perceive you.

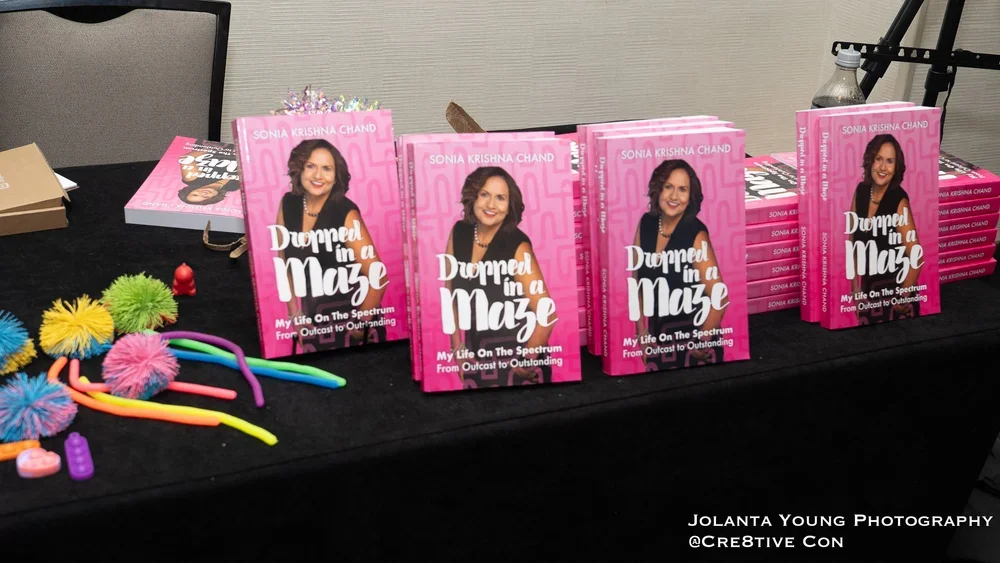

In my book, I provide detailed guidance on what's appropriate to share at different relationship stages and how to recognize when you're oversharing before it damages your reputation further.

Truth #6: Desperation Pushes People Away Instead of Drawing Them In

The Anxiety Spiral

As my birthday approached and people started canceling, my anxiety skyrocketed. I:

Reminded people constantly about the celebration

Felt physically ill from stress and cortisol buildup

Could barely eat or concentrate on anything else

Became increasingly frantic about making the fantasy happen

Why Desperation Repels

Desperation creates discomfort in others because:

It signals neediness that feels overwhelming to people who barely know you.

It creates pressure to fulfill expectations they never agreed to.

It makes them feel guilty for not caring as much as you want them to.

It highlights the imbalance in how you view the relationship versus how they view it.

The Therapist's Warning

My therapist, Dr. Theroux, tried to warn me: "Remember, Sonia, people don't like to keep hearing about the same thing again and again. Do your best to stay in the present."

She recognized I was becoming overeager and overexcited—classic signs of desperation that turn people off.

What Confidence Looks Like Instead

Confidence in social situations means:

Having plans but not being attached to specific people showing up

Being okay if people decline without taking it personally

Not reminding people repeatedly about your event

Having backup plans that don't depend on others' participation

Maintaining emotional stability regardless of who attends

This is incredibly difficult when you're lonely and desperate for connection. But desperation has the opposite effect of what you want—it pushes people away instead of drawing them in.

The Devastating Reality

The day of my 21st birthday, the last pieces fell apart:

Leila wasn't feeling well and couldn't come

Phaedra was eating dinner earlier than I could join

Nadia had to work and was told not to encourage alcohol consumption

Savannah had a mandatory sorority meeting

I ended up alone at a fast-food restaurant eating a fish sandwich and chocolate shake for my birthday dinner.

What Actually Builds Real Friendships

The Brutal Truth I Had to Learn

You can't force friendships into existence by planning elaborate events. Real friendships develop through:

Consistent, low-key contact over extended time periods.

Reciprocal effort where both people initiate and invest equally.

Shared experiences that happen organically, not through forced celebrations.

Gradual deepening of trust and emotional intimacy.

Natural compatibility that can't be manufactured through willpower.

What I Should Have Done Instead

Rather than planning an elaborate 21st birthday with acquaintances, I should have:

Focused on building one or two deeper friendships through regular, consistent contact.

Accepted my current social reality instead of trying to force it to match others' experiences.

Celebrated modestly in ways that matched my actual relationship status.

Used the milestone as motivation to build genuine friendships over the coming year, not as a deadline to manufacture them.

Worked with my therapist on realistic relationship-building strategies instead of fantasy fulfillment.

The Skills I Lacked

Ankita pointed out important skills I needed:

How to help a friend in need - When she hurt her foot and I rushed past to my exam, I should have said: "I'm so sorry you aren't feeling well. Is there anything I can do? I have an exam I need to rush to at the moment."

Understanding boundaries - Both my own and others', recognizing what's appropriate to share and when.

Standing up for myself - Which I was learning with Janet but needed to extend to other relationships.

Reading social situations - Understanding when someone is genuinely interested versus being polite.

These skills can't be learned overnight. They require practice, feedback, and often professional guidance.

Key Takeaways for Managing Expectations

Adjust Expectations to Match Reality

The most painful part of my 21st birthday wasn't being alone—it was the enormous gap between what I expected and what happened.

If I'd recognized that I had acquaintances, not friends, I could have:

Celebrated with family instead

Had modest plans that matched my social reality

Avoided the devastating crash when fantasy met reality

Quality Matters More Than Quantity

Stop measuring social success by:

Size of celebration

Number of people who attend your events

How your milestones compare to others' experiences

Start measuring it by:

Depth of a few genuine connections

Reciprocal investment in relationships

Quality of interactions, not quantity

Build Friendships Before Planning Celebrations

Celebrations are the result of established friendships, not the catalyst for creating them.

Before planning group events, ask:

Do these people regularly spend time with me outside structured settings?

Have they invited me to their events?

Is there reciprocal effort in maintaining contact?

Would they notice if I disappeared from their lives?

If the answers are no, you're dealing with acquaintances who won't show up for celebrations.

Learn From Each Painful Experience

My 21st birthday was humiliating. Eating that fish sandwich alone while imagining others celebrating with their friend groups felt like rock bottom.

But it taught me critical lessons:

Fantasy doesn't create reality

Desperation pushes people away

You can't force friendships on your timeline

Acquaintances won't show up like friends do

These lessons, painful as they were, eventually helped me build genuine friendships by adjusting my approach.

Protect Yourself From Repeated Devastation

If you keep experiencing this pattern:

Work with a therapist on realistic relationship-building

Learn to distinguish polite responses from actual commitments

Stop building elaborate fantasies to cope with loneliness

Focus on one or two potential friends at a time

Accept that building genuine friendships takes years, not weeks

Ready to learn the complete story of my 21st birthday disaster and what I eventually learned about building real friendships instead of manufacturing fake ones? My book provides the full account, get your copy today.

Moving Forward

The night didn't end with the fish sandwich. I eventually went to the bar where my roommate was celebrating with her friends. I got lost in the sensory overload—the lights, the music, the crowds. My roommate kept telling me to drink more. I wanted to forget the harsh reality through alcohol.

I heard the DJ announce other people's birthdays over the stereo. Each announcement felt like a bee sting—a reminder that other people had the tight friend groups celebrating them that I desperately wanted but didn't have.

That night crystallized a brutal truth: you can't drink away loneliness. You can't force friendships through elaborate planning. You can't manufacture belonging through sheer determination.

What you can do is learn from the devastation, adjust your approach, and slowly build the genuine connections that eventually replace the fantasy.

For the complete journey from devastating birthday disasters to eventually building real friendships—including all the mistakes I made, lessons I learned, and strategies that actually worked—my book provides everything you need to stop repeating this painful pattern.

Get your copy today and learn how to build realistic expectations that protect you from crushing disappointment.

5 Reasons Why Your Gut Knows Before Your Brain Does (And How to Finally Trust It)

Have you ever had a bad feeling about something but talked yourself out of it? Ignored the warning signs because you thought you were being paranoid? Agreed to plans that made your stomach turn because you didn't want to seem rude or difficult?

Your gut was screaming at you to say no. But your brain—trained by years of people-pleasing, low self-esteem, and desperate need for acceptance—overruled it.

For autistic people and anyone who's spent years being rejected or told they're "too sensitive," learning to trust your gut instinct feels nearly impossible. We've been conditioned to doubt ourselves, to assume our discomfort is our problem to fix, to override our internal warning system in favor of what others expect from us.

But here's what I learned the hard way: your gut knows things your brain hasn't processed yet. It picks up on patterns, energy shifts, and danger signals that your conscious mind hasn't caught up to. And when you consistently ignore it to please others or avoid conflict, you end up in situations that harm you.

Table of Contents

Reason #1: Your Gut Recognizes Patterns Your Brain Hasn't Named Yet

Reason #2: Your Body Responds to Energy Before Your Mind Analyzes It

Reason #3: Low Self-Esteem Convinces You to Ignore Warning Signals

Reason #4: People-Pleasing Overrides Self-Protection

Reason #5: Your Gut Protects You From What You Can't Yet Articulate

How to Start Trusting Your Gut Instinct

Key Takeaways for Building Self-Trust

Reason #1: Your Gut Recognizes Patterns Your Brain Hasn't Named Yet

The Week of Bad Feelings

When Janet asked to come over and stay the night, something inside me immediately screamed "no." It wasn't logical. I couldn't point to a specific reason. But my gut was screaming: "Cancel your plans now!"

All week leading up to that Friday, the bad feeling intensified. It wasn't anxiety about hosting or nervousness about having company. It was a visceral warning that something was wrong.

Why Your Gut Knows First

Your gut instinct operates on pattern recognition that happens below conscious awareness. It processes:

Past experiences with this person Every snippy comment, every backhanded compliment, every time they made you feel small—your gut remembers even when your brain tries to give people the benefit of the doubt.

Behavioral patterns Your gut notices consistency. If someone consistently makes you feel bad, your gut expects more of the same—even if your brain hopes "this time will be different."

Energy shifts Changes in how someone interacts with you register in your body before your brain consciously processes them. Your gut noticed Janet wasn't in a good mood before she even articulated it.

Danger signals Your nervous system is wired for survival. When it detects threat patterns—even emotional or social threats—it sends warning signals through physical sensations.

What Happens When You Ignore It

I knew my gut was right. But my low self-esteem and self-doubt overruled the warning. I said "yes" when everything inside me was screaming "no."

The result? Exactly what my gut predicted:

Janet showed up in a bad mood

She made snippy, demanding comments

She picked a fight over breakfast

She stormed out like a child having a tantrum

My gut knew. I just didn't trust it yet.

Reason #2: Your Body Responds to Energy Before Your Mind Analyzes It

The Physical Warning System

When you have a "bad feeling" about something, it's not just emotional—it's physical. Your body is responding to information your conscious mind hasn't processed yet.

Common physical gut reactions include:

Stomach tightening or nausea

Chest heaviness or tightness

Jaw clenching or teeth grinding

Shoulders tensing up

Heart rate increasing

Feeling suddenly drained or exhausted

An urge to leave or create distance

Why This Happens

Your nervous system picks up on:

Micro-expressions and body language Even if you struggle with reading faces (common for autistic people), your subconscious registers micro-expressions, tone shifts, and body language that signal hostility, insincerity, or danger.

Tone and vocal patterns The way someone says something carries more information than the words themselves. Your gut hears the edge in someone's voice before your brain consciously recognizes they're being passive-aggressive.

Environmental stress When someone brings negative energy into your space, your body responds to the shift in atmosphere. You feel it physically before you can name it.

Incongruence When someone's words don't match their energy, your gut knows something is off. Janet might have asked to come over in a friendly way, but the energy behind it wasn't friendly—and my body knew.

The Autistic Experience

Many autistic people are told they're "too sensitive" or "reading too much into things." But often, we're picking up real information through sensory and energetic channels that neurotypical people dismiss.

Learning to honor these physical responses instead of dismissing them is crucial for self-protection.

In my book, I detail the complete weekend with Janet and how my body was trying to protect me at every step. Learning to recognize and honor these physical warning signals transformed my ability to protect myself from toxic people and situations.

Reason #3: Low Self-Esteem Convinces You to Ignore Warning Signals

The Internal Battle

When my gut screamed "cancel your plans," my low self-esteem fought back with powerful counter-arguments:

"You're being paranoid"

"Give her a chance"

"You're too sensitive"

"You're lucky anyone wants to spend time with you"

"Don't be difficult"

"What if you're wrong?"

Low self-esteem convinced me that my gut feeling was the problem, not Janet's behavior.

How Low Self-Esteem Sabotages Intuition

It makes you second-guess yourself When you don't trust yourself in general, you don't trust your instincts about specific situations.

It prioritizes others' comfort over your safety Low self-esteem teaches you that other people's feelings matter more than your own boundaries and wellbeing.

It reframes warning signals as character flaws Instead of "this person makes me uncomfortable," low self-esteem says "I'm uncomfortable because something is wrong with me."

It creates fear of being seen as difficult You'd rather endure a bad situation than risk being perceived as rude, picky, or high-maintenance.

It convinces you that you deserve poor treatment Years of rejection and bullying create a belief that toxic behavior is what you should expect and accept.

The Cost of Self-Doubt

By doubting my gut and saying yes to Janet's visit, I:

Spent a week with escalating anxiety

Endured a miserable Friday night

Got into a fight over breakfast

Had to deal with her tantrum and dramatic exit

All of this could have been avoided if I'd trusted that bad feeling and said "I'm not available that night."

Breaking the Pattern

Learning to trust your gut requires rebuilding self-esteem so that your inner voice becomes stronger than others' expectations.

This means practicing:

Valuing your comfort as much as others' comfort

Recognizing that "no" is a complete sentence

Understanding that protecting yourself isn't being difficult

Believing your feelings are valid data, not character flaws

Reason #4: People-Pleasing Overrides Self-Protection

The "I Didn't Know How to Say No" Problem

When Janet asked to stay over, I immediately knew I didn't want her to. But I said "Sure" anyway.

Why? Because I didn't know how to say no.

Not because I literally didn't know the word exists. But because years of conditioning had taught me that:

Saying no makes you selfish

Declining invitations means you're unfriendly

Setting boundaries means you're difficult

Protecting yourself means you're rude

The People-Pleasing Trap

People-pleasing is particularly common among:

Autistic people We're often taught from childhood that our natural responses are "wrong" and we need to accommodate neurotypical expectations, even at our own expense.

People with trauma histories Bullying, rejection, and social isolation create hypervigilance about others' reactions. We learn to prioritize keeping others happy to avoid further rejection.

Women and people socialized as women Societal conditioning teaches that being agreeable, accommodating, and pleasant is more important than honoring your own needs and boundaries.

Anyone with low self-worth When you don't value yourself, you treat others' preferences as more important than your own wellbeing.

The Physical Toll

People-pleasing doesn't just create bad social situations—it creates physical and emotional stress:

Chronic anxiety from ignoring your needs

Resentment that builds toward others

Exhaustion from constantly performing

Difficulty identifying what you actually want

Erosion of self-trust over time

What Changed Everything

When Janet stormed out over the breakfast misunderstanding, I didn't feel sad—I felt relieved. And then I felt proud.

I had finally stood up for myself. I had spoken my mind. I had stopped accommodating unreasonable behavior.

Instead of feeling guilty or chasing after her to apologize, I celebrated. I treated myself to a nice meal. I honored the fact that I had finally prioritized my own wellbeing over someone else's mood.

The complete story of ending this toxic friendship and what I learned about setting boundaries is detailed in my book. These lessons about people-pleasing versus self-protection changed every relationship I had going forward.

Reason #5: Your Gut Protects You From What You Can't Yet Articulate

The Thing About Gut Feelings

Gut feelings are frustrating because they often can't be explained logically. You just know something is off, but you can't always point to concrete evidence.

This makes them easy to dismiss, especially for autistic people who are used to wanting clear, logical explanations for everything.

What Your Gut Knows

Your gut processes information that your conscious mind hasn't caught up to yet:

Emotional patterns Janet had been consistently dismissive, critical, and condescending. My gut knew this pattern would continue. My brain hoped it wouldn't.

Power dynamics My gut recognized that Janet saw me as someone she could use as a punching bag. My brain wanted to believe she was my friend.

Incompatibility Deep down, I knew Janet and I weren't compatible as friends. My gut was trying to protect me from continuing an unhealthy relationship.

Future consequences Some part of me knew that if I said yes to this visit, I'd regret it. My gut was trying to save me from that outcome.

The Gift of Hindsight

Looking back, every bad feeling I had was correct:

The week of increasing dread? Accurate prediction of how the visit would go.

The sense that I should cancel? Exactly right.

The physical discomfort? Warning that this person brought toxic energy.

The relief when she left? Confirmation that my gut had been protecting me all along.

Why We Ignore It Anyway

Even when gut feelings prove accurate again and again, we still ignore them because:

We're taught to prioritize logic over feeling "That's not a good enough reason" dismisses intuition as invalid.

We fear being wrong What if you say no and miss out on something good? (Spoiler: Your gut is rarely wrong about danger.)

We've been gaslit When people tell you you're "too sensitive" or "overthinking," you learn to distrust your perceptions.

We want to be accommodating Especially for autistic people who've been told we're "difficult," we overcompensate by being overly flexible with others.

Learning to Listen

The turning point came when I finally honored my gut:

When Janet stormed out, I didn't chase her. I didn't call to apologize. I didn't try to fix it.

I celebrated getting rid of someone who treated me poorly.

That moment taught me: My gut was protecting me. I just needed to start listening.

How to Start Trusting Your Gut Instinct

Step 1: Notice Physical Sensations

Start paying attention to how your body responds to:

Specific people

Social invitations

Requests for your time or energy

Situations that make you uncomfortable

Common gut signals:

Stomach tightening

Chest heaviness

Sudden fatigue

Jaw clenching

Desire to leave or create distance

Don't dismiss these as "just anxiety." They're information.

Step 2: Track Patterns

Keep a journal of:

When you had a bad feeling about something

Whether you honored it or ignored it

What actually happened

Over time, you'll see that your gut is usually right. This builds trust in your instincts.

Ready to learn the complete story of how trusting my gut transformed my college experience and beyond? My book details the full journey from people-pleasing to self-protection, including specific strategies for distinguishing anxiety from intuition and building the self-trust that changes everything.

Step 3: Practice Small Nos

Start with low-stakes situations:

"I'm not available that day"

"That doesn't work for me"

"I need to think about it"

"I'm going to pass this time"

Notice that saying no doesn't create the catastrophes you fear. This builds confidence in setting boundaries.

Step 4: Challenge the Voice of Self-Doubt

When you have a gut feeling and self-doubt tries to override it, ask:

"What if my gut is right and self-doubt is wrong?"

"What's the worst that happens if I honor this feeling?"

"Am I prioritizing someone else's comfort over my safety?"

"Would I give this advice to a friend in the same situation?"

Step 5: Separate Anxiety From Intuition

This is tricky, especially for people with anxiety disorders. Here's a general guide:

Anxiety:

Spirals and catastrophizes

Creates "what if" scenarios about the future

Feels chaotic and overwhelming

Isn't connected to specific present-moment information

Intuition:

Is calm and clear (even if uncomfortable)

Focuses on present-moment data

Provides specific direction ("don't do this")

Feels grounded in your body

Both can create physical sensations, but intuition feels more like information while anxiety feels like panic.

Step 6: Honor the Gut Feeling Even Without Evidence

You don't need to justify your gut feelings with concrete evidence. "This doesn't feel right" is sufficient reason to:

Decline an invitation

Leave a situation

End a relationship

Change your mind

You're allowed to protect yourself based on instinct, not just provable facts.

Step 7: Celebrate When You're Right

Every time you honor your gut and it proves correct, acknowledge it:

"I knew that person wasn't trustworthy and I was right." "I didn't want to go and I'm glad I didn't." "My gut told me to leave and that was the right call."

This positive reinforcement strengthens the connection between gut feelings and action.

Key Takeaways for Building Self-Trust

Your Gut Deserves Respect

After years of being told we're "too sensitive" or "overthinking," autistic people and trauma survivors often dismiss our instincts as invalid.

But your gut reactions are:

Valid data about your environment

Protection mechanisms that evolved to keep you safe

Information your subconscious processed before your conscious mind caught up

They deserve to be honored, not overridden.

Liberation Comes From Self-Protection

When I finally stood up to Janet and felt relief instead of guilt, everything changed. That summer became one of the most liberating periods of my life because I:

Eliminated toxic people

Started meeting new friends

Built confidence in my judgment

Learned that protecting myself felt good, not selfish

The liberation didn't come from having more friends. It came from trusting myself enough to say no to people who treated me poorly.

Low Self-Esteem Is Your Gut's Biggest Enemy

The biggest obstacle to trusting your gut isn't lack of intuition—it's low self-esteem convincing you that:

Your feelings don't matter

Others' comfort is more important than yours

You should be grateful for any social connection

Protecting yourself makes you difficult

Building self-esteem doesn't just make you feel better—it allows you to finally hear the wisdom your gut has been offering all along.

People-Pleasing Puts You in Danger

Every time you override your gut to please someone else, you:

Teach yourself that your needs don't matter

Put yourself in situations that harm you

Reinforce the pattern of self-abandonment

Weaken your ability to trust future gut feelings

Breaking the people-pleasing pattern is essential for self-protection.

"No" Is Protection, Not Rejection

Saying no when your gut screams at you isn't:

Being mean

Being difficult

Being antisocial

Missing out on opportunities

It's:

Honoring your needs

Protecting your energy

Respecting your boundaries

Practicing self-care

The right people will respect your boundaries. The wrong people will prove your gut right by getting angry when you set them.

Ready to learn the complete story of how trusting my gut transformed my college experience and beyond? My book details the full journey from people-pleasing to self-protection, including specific strategies for distinguishing anxiety from intuition and building the self-trust that changes everything.

Moving Forward

That summer when I finally trusted my gut and ended the friendship with Janet, everything shifted. I made new friends—Savannah from my Middle Eastern History class, Tia the international student from Brazil—who treated me with genuine kindness.

My confidence built. I started working out at the gym, feeling good in my clothes, and looking forward to what was coming next. I felt hopeful and happy.

None of that would have been possible if I'd continued ignoring my gut and tolerating toxic people.

Your gut is always trying to protect you. The question is: will you finally start listening?

The next time you get that sinking feeling, that tightness in your stomach, that voice saying "something is off"—trust it. Even if you can't explain it logically. Even if it means disappointing someone. Even if it makes you seem difficult.

Your gut knows. It's been trying to tell you. It's time to start believing it.

For the complete journey from self-doubt to self-trust, including detailed accounts of learning to set boundaries, eliminate toxic relationships, and build genuine confidence—get my book today.

7 Signs Someone Isn't Really Your Friend (Lessons from College Life on the Autism Spectrum)

College is supposed to be where you find your people. Where lifelong friendships form over late-night study sessions and shared experiences. Where you finally escape the social hierarchy of high school and start fresh.

But what if you can't tell who's genuinely interested in being your friend versus who's just being polite? What if you're so desperate for connection that you miss obvious red flags? What if the people you think are your friends are actually talking about you behind your back?

As a newly diagnosed autistic college student navigating a campus of 40,000 people, I learned these lessons the hard way. The social confusion didn't end with my diagnosis—in some ways, it got harder because I was now hyperaware of my differences while still lacking the skills to navigate complex social dynamics.

If you're autistic, socially isolated, or simply struggling to distinguish genuine friendship from fake niceness, these warning signs will help you protect yourself from people who don't have your best interests at heart.

Table of Contents

Sign #1: They Only Compliment You With Backhanded Comments

Sign #2: They Dismiss Your Problems While Claiming to Support You

Sign #3: They're Nice to Your Face But Talk Behind Your Back

Sign #4: They Give You Contradictory or Harmful Advice

Sign #5: They Make You Feel Compared and "Less Than"

Sign #6: They Tell You That You Make Them Uncomfortable

Sign #7: They Keep You Around Out of Obligation, Not Genuine Interest

How to Spot Genuine Friendship

Key Takeaways for Autistic People Navigating Friendships

Sign #1: They Only Compliment You With Backhanded Comments

What a Backhanded Compliment Looks Like

A backhanded compliment appears positive on the surface but contains a hidden insult or criticism. It's praise that makes you feel worse, not better.

My "friend" Janet was a master of this technique:

"You're very intelligent, but you shouldn't need other people to tell you that."

I never asked for the compliment, yet she managed to turn it into criticism about my supposed need for validation.

Why This Is a Red Flag

Real friends celebrate your strengths without adding conditions or criticisms. They don't use compliments as vehicles for putting you down.

Backhanded compliments serve several purposes for fake friends:

They maintain superiority. By adding criticism to praise, they position themselves as the one who "sees clearly" while you remain flawed.

They keep you insecure. You can't fully enjoy the compliment because it's paired with something negative, keeping you off-balance and seeking their approval.

They appear nice to others. If called out, they can point to the "compliment" part and claim you're being too sensitive about the criticism.

Common Backhanded Compliments to Watch For

"You're so brave to wear that"

"You're pretty for someone who..."

"You're smart, but you lack common sense"

"That's a great idea, considering you don't have experience"

"You're doing better than I expected"

What Genuine Compliments Sound Like

Real friends give straightforward praise without qualifiers:

"You're really intelligent"

"I love that outfit on you"

"That was a brilliant idea"

"You did amazing on that project"

If someone consistently packages compliments with criticism, they're not your friend—they're your critic.

Sign #2: They Dismiss Your Problems While Claiming to Support You

The "I'm Here for You" Lie

Janet loved to position herself as my supportive friend. But when I actually needed support, her response revealed her true feelings.

When I was hurt that my friend Alisha hadn't responded to my emails, I called Janet for perspective. She started kindly: "I'm so sorry to hear that Alisha did that to you. You don't deserve to be treated that way."

Then she dropped the bomb.

"The problem with you is that you only like pretty people with long black hair as your friends. Alisha was beautiful, thin, and everything you wanted to be. That's why you wanted her to be your friend. But you don't consider me a friend, and I'm here for you, always. This is some shit. This is really some shit."

The Pattern of Fake Support

Fake friends follow a predictable pattern:

Step 1: Express initial sympathy to appear supportive Step 2: Pivot to criticizing you instead of the situation Step 3: Make the problem about themselves and what you're not giving them Step 4: Leave you feeling worse than before you shared

Why They Do This

People who dismiss your problems while claiming to support you are often:

Jealous. Your other friendships threaten them because they want to be your only source of support (and control).

Resentful. They feel you owe them something for "putting up with you" and use your vulnerable moments to extract payment.

Competitive. They see your pain as an opportunity to position themselves as superior or more valued.

Manipulative. They keep you emotionally dependent by being the only person you feel you can turn to, then make you feel guilty for needing support.

What Real Support Looks Like

When I learned that Alisha's father had undergone major cardiac surgery, I felt terrible for jumping to conclusions. My therapist, Dr. Theroux, had helped me see other possibilities before assuming rejection.

Real support involves:

Asking questions before making judgments

Offering alternative perspectives

Validating your feelings while helping you see the full picture

Not making your problem about themselves

In my book, I detail the complete dynamic with Janet and how this toxic friendship finally ended. Understanding these patterns can save you years of emotional manipulation from people who claim to be friends.

Sign #3: They're Nice to Your Face But Talk Behind Your Back

The Double Life

One of my floormates organized group events and invited me to dinner and Valentine's Day activities. She seemed friendly and interested in getting to know me.

Later in the semester, she admitted to my face: "You make people feel really uncomfortable. You make me feel very uncomfortable."

This was the same person who'd been smiling at me, inviting me to events, and acting like we were friends. Behind my back, she was telling people how "repulsed" she was by me.

Why Autistic People Are Vulnerable to This

Autistic people often struggle to detect:

Fake enthusiasm. We take people at face value. If someone acts friendly, we believe they're being friendly.

Social performance. We don't realize that some people maintain pleasant facades while harboring completely different feelings.

Group dynamics. We miss when someone is including us for appearances while simultaneously mocking us to others.

Subtle cues. The microexpressions, tone shifts, and body language that signal insincerity fly under our radar.

Warning Signs Someone Is Two-Faced

Others warn you that people are "laughing at you" without specifics

You're included in group activities but never invited to smaller hangouts

People seem friendly individually but ignore you in groups

You hear through others that someone has been talking about you

Someone's behavior toward you changes drastically depending on who else is present

The "Common Courtesy" Trap

Janet once screamed at me: "People who meet you are only acting out of common courtesy, something learned at home. Not everybody who is nice to you is trying to be your friend."

This was actually valuable information buried in a toxic delivery. Many autistic people mistake politeness for friendship because:

We don't have extensive experience distinguishing the two

We're desperate for connection after years of isolation

We take social interactions at face value

We assume good intentions because that's how we operate

How to Protect Yourself

Don't share personal information with people you just met

Watch for consistency over time—do actions match words?

Notice if invitations are genuine or performative

Trust people who warn you about others talking behind your back

Remember that silence in group settings often means agreement with gossip

Sign #4: They Give You Contradictory or Harmful Advice

When "Help" Makes Things Worse

After Janet dismissed Alisha's family emergency—"Then what is the mother there for? To sit and look pretty?! Bullshit!!"—I realized her advice was designed to isolate me from other friendships.

She wanted to be my only friend so she could continue using me as an emotional punching bag.

The Advice Test

Good advice helps you. Bad advice serves the advice-giver's interests.

When evaluating advice from a supposed friend, ask:

Does this advice help me or them? If following the advice would make you more dependent on them or isolated from others, it's not good advice.

Is this advice realistic? "Just be confident" isn't actionable advice. "Practice one conversation starter this week" is.

Does this advice consider my situation? Generic advice that ignores your autism, social challenges, or specific circumstances isn't helpful.

Do I feel worse after receiving this advice? Real support leaves you feeling encouraged or clearer. Fake support leaves you confused and deflated.

The Danger of Contradictory Advice

Janet told me different things at different times:

"You think everybody is your friend" (criticizing me for being too trusting)

"You don't consider me a friend" (criticizing me for not valuing her enough)

This kept me off-balance, never sure what I was doing wrong, always trying to please her.

What Good Advice Sounds Like

My therapist, Dr. Theroux, offered helpful guidance:

"Instead of jumping to conclusions, why don't you first find out what's happening with Alisha? Maybe send her an email."

She helped me:

Challenge my all-or-nothing thinking

Consider alternative explanations

Take action based on facts, not assumptions

Communicate directly rather than spiraling

The difference between helpful therapeutic guidance and toxic friendship advice is night and day. In my book, I share how working with Dr. Theroux taught me to recognize when advice was actually helpful versus when it was designed to control me.

Sign #5: They Make You Feel Compared and "Less Than"

The Constant Comparisons

My roommate Tracy told me: "Part of making friends is knowing who you are and what you stand for. People don't come talk to you much because they don't see the confidence in you and a person who knows who she is; whereas, people love to come to talk to me and others because we know who we are."

Every conversation left me feeling like I didn't measure up to her social success.

Why Comparisons Are Harmful

Real friends don't:

Constantly point out your deficits compared to them

Make their social success a benchmark for your failure

Position themselves as the standard you should aspire to

Use your differences to elevate themselves

The "You Should Know By Now" Trap

Tracy would say things like: "You should know how to read people by now. You are in college."

This assumes everyone develops social skills on the same timeline, ignoring that:

Autistic people develop social skills differently and later

Not having friends growing up means less practice with friendships

College isn't a magic cure for years of social isolation

Shaming someone for not knowing something doesn't teach them

What Supportive Friends Do Instead

Supportive friends:

Meet you where you are without judgment

Offer specific help rather than vague criticism

Share their knowledge without implying you're behind

Celebrate your progress instead of comparing you to others

When someone constantly makes you feel inferior, they're not trying to help you improve—they're trying to feel superior.

Sign #6: They Tell You That You Make Them Uncomfortable

The Uncomfortable Confession

Lucy, who'd invited me to multiple floor events, eventually told me: "You make people feel really uncomfortable. You make me feel very uncomfortable."

When I asked what I did, she said: "You tend to invite yourself to things you aren't invited to."

I genuinely didn't remember doing this except once, when I asked to join her on a store trip after we'd had brunch together that same day.

The Problem With Vague Accusations

When someone tells you that you make them uncomfortable without:

Specific examples of what you did

Clear explanation of what bothered them

Actionable feedback on what to change

Compassion for your perspective

They're not trying to help you improve. They're trying to make you feel bad while appearing reasonable.

The Double Standard

Lucy had:

Invited me to multiple events

Gone to brunch with me

Organized floor activities that included me

Acted friendly for months

Then suddenly declared I made her uncomfortable—without explaining why she'd been including someone who supposedly made her so uncomfortable.

Why Autistic People Get Blamed

Autistic people are often told we make others uncomfortable because:

We're enthusiastic about potential friendships. Neurotypical people see this as "too much" or "desperate."

We don't pick up on subtle rejection. When someone doesn't explicitly say no, we assume they mean yes.

We take invitations literally. If you invite us once, we think you meant it. We don't realize it was performative.

We ask clarifying questions. This can be perceived as not "getting it" when social rules are supposed to be obvious.

What To Do When Someone Says This

If someone tells you that you make them uncomfortable:

Ask for specific examples

Request actionable feedback

Consider whether their discomfort stems from your autism, not actual wrongdoing

Evaluate whether this person has been genuine with you

Remember that not everyone will like you, and that's okay

Sometimes people's discomfort says more about them than you.

Sign #7: They Keep You Around Out of Obligation, Not Genuine Interest

The Moral Obligation Friend

Janet made it clear she felt morally obligated to be my friend. She stayed connected not because she enjoyed my company but because abandoning someone with my challenges would make her look bad.

This manifested in:

Resentment when I needed support

Keeping score of everything she did for me

Making me feel like I owed her for tolerating me

Treating our friendship like charity work

Signs Someone Feels Obligated

They emphasize how much they do for you. Real friends don't keep score or remind you how much they sacrifice to be your friend.

They act inconvenienced by your needs. When you reach out for support, they respond with sighs, eye rolls, or comments about how they're always there for you.

They compare themselves favorably to your other friends. "At least I'm here for you, unlike [other person]."

They make you feel guilty for wanting friendship. Your desire for connection becomes a burden they heroically bear.

The Gratitude Trap

People who feel obligated to be your friend often expect excessive gratitude:

For including you in activities

For responding to your messages

For "dealing with" your autism

For being the "only" person who tolerates you

Real friends don't require constant thanks for basic friendship behaviors.

Why This Happens to Autistic People

Autistic people are particularly vulnerable to obligation-based friendships because:

Years of rejection make us grateful for any social connection

We've internalized messages that we're difficult to be around

We don't recognize when someone views us as charity work

We mistake obligation for loyalty

Breaking Free

If someone makes you feel like a burden they've nobly chosen to carry:

Recognize that this isn't friendship

Stop investing emotional energy in maintaining the relationship

Find people who genuinely enjoy your company

Remember that you deserve friends who want you around, not ones who tolerate you

My book details how the friendship with Janet finally ended and what I learned about recognizing obligation-based relationships before investing years in them. This lesson transformed how I approach friendships today.

How to Spot Genuine Friendship

After all these fake friendships, I did eventually find genuine connections. Here's what real friendship looked like:

Alisha: The Real Friend

When Alisha didn't respond to my emails, my immediate thought was rejection. My therapist helped me consider other possibilities.

It turned out Alisha's father had undergone major cardiac surgery. She wasn't ignoring me—she was dealing with a family crisis.

Real friends:

Have legitimate reasons when they're less available

Don't play games with your feelings

Communicate when they can

Pick up where you left off without resentment

Wendy: The Encouraging Roommate

My first roommate, Wendy, was genuinely supportive:

She reassured me about starting the semester with a full campus

She didn't compare herself to me

She was happy for me when I got to transfer dorms, even though it meant losing her roommate

She had "impeccable manners" and a "good aura"

Real friends:

Encourage rather than criticize

Are happy for your successes

Don't see your growth as a threat

Create a comfortable, safe energy

Key Takeaways for Autistic People Navigating Friendships

You Don't Have to Accept Crumbs

Years of rejection taught me to be grateful for any social connection, even toxic ones. But accepting fake friendship out of desperation only prolongs loneliness.

It's better to be alone than to be with people who:

Criticize you constantly

Talk about you behind your back

Keep you around out of obligation

Make you feel worse about yourself

Not Everyone Has Your Best Interests at Heart

This is a hard lesson for autistic people who assume good intentions. Some people will:

Use your naivety against you

Take advantage of your difficulty reading social situations

Exploit your desperation for connection

Maintain friendly facades while harboring resentment

Trust Your Gut, But Learn to Read It

Many autistic people experience anxiety that makes it hard to distinguish genuine intuition from fear. But there's usually a difference between:

Anxiety: "What if they don't like me?" Intuition: "Something feels off about how they treat me."

Learning to recognize this difference takes time and often requires:

Therapy to process past experiences

Social skills training to understand patterns

Support from people who can offer objective perspectives

Practice trusting yourself when something doesn't feel right

Quality Over Quantity Always

Janet asked me: "What sounds better? One friend whom you could trust or having a group where you don't even know if you could trust them?"

She was right about one thing (even if her motives were wrong): one genuine friend is worth more than an entire group of fake ones.

Don't measure your social success by:

Number of friends

Size of your friend group

How busy your social calendar is

Measure it by:

How you feel after spending time with people

Whether friendships are reciprocal

If people celebrate you rather than criticize you

Whether you can be yourself without fear of judgment

Social Skills Take Time—And That's Okay

Tracy said: "You should know how to read people by now. You are in college."

But social skills aren't age-dependent—they're experience-dependent. If you didn't have friends growing up, you're learning in college what others learned in childhood.

This doesn't make you behind. It makes you on a different timeline.

Be patient with yourself while learning to:

Distinguish genuine interest from politeness

Recognize when someone is two-faced

Set boundaries with people who make you feel bad

Trust your instinctive responses to people's energy

Ready to learn the complete story of navigating college friendships as a newly diagnosed autistic person? My book provides detailed accounts of these relationships, what I learned from each experience, and practical strategies for protecting yourself from fake friends while finding genuine connections.

Get your copy today and learn from my mistakes so you don't have to repeat them.

Final Thoughts

Looking back at my sophomore year of college, I wish someone had taught me these red flags before I invested so much emotional energy in people who didn't deserve it.

Janet wasn't my friend—she was my critic who enjoyed feeling superior to someone she viewed as socially inferior.

Lucy wasn't my friend—she was someone who included me out of politeness while complaining about me behind my back.

Tracy wasn't my friend—she was a roommate who saw my social struggles as an opportunity to position herself as more evolved.

But Alisha, Wendy, and even brief connections like Phaedra showed me what real friendship could look like. Those glimpses of genuine connection kept me going through the lonely times and taught me that not everyone would treat me poorly.

The maze post-diagnosis wasn't easier than before—in some ways, it was harder because I was now hyperaware of my differences. But with each fake friendship that ended and each genuine connection that formed, I learned to navigate it better.

You will too. It just takes time, practice, and the willingness to walk away from people who don't deserve access to you.

For the complete journey through college friendships, toxic relationships, and learning to recognize genuine connection—plus practical strategies for every situation I faced—get my book today. You'll find validation, wisdom, and tools that will transform how you approach friendships as an autistic person.

5 Things That Happen When You Finally Get Your Autism Diagnosis

Getting an autism diagnosis as an adult is nothing like getting diagnosed as a child. There's no early intervention plan waiting for you. No teachers adjusting their approach. No parents advocating on your behalf.

Instead, you're sitting in a neuropsychologist's office at age 19, finally understanding why life has felt like navigating a maze blindfolded while everyone else seemed to have a map.

When I received my Asperger's Syndrome diagnosis (now classified as autism spectrum disorder) at the beginning of my fall semester in college, I experienced a flood of contradictory emotions. Relief mixed with grief. Validation tangled with frustration. Freedom alongside pain.

If you're pursuing a diagnosis, recently diagnosed, or supporting someone through this process, understanding what comes next can help you navigate the complex emotional landscape that follows those life-changing words: "You're autistic."

Table of Contents

The Blindfold Finally Comes Off

When Professionals Tell You What You Already Knew

The Double-Edged Sword of Vulnerability Awareness

Navigating Identity: "Why Couldn't I Be Normal?"

What Depression Couldn't Explain

Moving Forward After Diagnosis

Key Takeaways for Late-Diagnosed Adults

1. The Blindfold Finally Comes Off

You've Been Lost in a Maze Your Entire Life

Before diagnosis, you've spent years—maybe decades—knowing something was different about you but lacking the language to explain it. You've heard:

"You're too sensitive"

"You just need to try harder socially"

"Everyone struggles with this"

"You're being dramatic"

"It's just anxiety/depression"

You've blamed yourself for social failures, sensory overwhelm, and difficulties that seemed easy for everyone else. You've internalized the message that you're broken, defective, or simply not trying hard enough.

Suddenly, the Map Appears

Diagnosis provides the framework that makes everything make sense. All those puzzle pieces that never seemed to fit together suddenly form a coherent picture.

The strict routines you needed weren't "being difficult"—they were accommodations for autism.

The sensory issues that made certain clothes unbearable weren't "being picky"—they were legitimate neurological responses.

The social confusion that left you friendless wasn't "being weird"—it was the result of processing social information differently.

That realization brings grief alongside the relief.

In my book, I explore the complete emotional journey of receiving an autism diagnosis in college and how it shaped my understanding of everything that had happened in the years leading up to that moment. If you're navigating similar territory, knowing you're not alone in these contradictory feelings makes all the difference.

2. When Professionals Tell You What You Already Knew

The Testing Process Confirms Your Suspicions

By the time I sat down for my diagnosis appointment, I'd already completed extensive psychological testing. The neuropsychologist reviewed:

Test results showing developmental delays and autistic traits

My entire history from childhood through college

Feedback from the summer internship where my immature behavior had been documented

She asked pointed questions: "How do you think your behavior came off this past summer?"

"That I didn't live up," I answered honestly.

"Do you think it is typical for people your age?" she pressed.

"No," I admitted.

Hearing the Truth Out Loud Hurts

"That behavior is very much like a child," she said directly.

Even though I knew this on some level, hearing it stated so plainly was embarrassing. The gap between my chronological age and my social-emotional development was now officially documented, not just privately suspected.

You Learn About Vulnerabilities You Didn't Know You Had

The neuropsychologist didn't just confirm autism. She pointed out specific vulnerabilities:

Naivety: "You are a bit naive, as shown by the tests. You also are immature for your age, which sets you up big time."

Risk of exploitation: "You are more at risk of being taken advantage of and used."

Susceptibility in social situations: "I strongly urge you to think twice before you even think of picking up a drink. You could easily be made to laugh and be the one made to dance on a table while everyone enjoys fun at your expense."

The Warning About College Party Culture

The neuropsychologist knew my university had a significant party scene. Her stern warning wasn't meant to shame me—it was meant to protect me.

Autistic people, especially those who are naive and desperate for social acceptance, are prime targets for exploitation. People can:

Manipulate you into doing embarrassing things for their entertainment

Take advantage of your literal thinking and trust

Use your desire to fit in against you

Exploit your difficulty reading social situations

Hearing these vulnerabilities spelled out was sobering. I went from relief at having a diagnosis to fear about how exposed I'd been all along.

What Professionals See That You Don't

The testing revealed things I hadn't fully recognized about myself:

Developmental delays that put me behind my peers emotionally

Autistic traits that explained my social struggles

Naivety that made me vulnerable to manipulation

Immaturity that others had noticed but I hadn't fully acknowledged

Sometimes the hardest part of diagnosis isn't the label itself—it's confronting the specific ways your differences have made life harder and put you at risk.

3. The Double-Edged Sword of Vulnerability Awareness

You Suddenly Realize How Many Times You've Been Used

Once the neuropsychologist explained my naivety and vulnerability to exploitation, my mind immediately went to past experiences:

The "friends" who invited me to parties just to see my house, not to spend time with me.

The people who prompted me to act out in middle school for their entertainment.

The classmates who manipulated me into doing embarrassing things while everyone laughed.

The arranged friendship that turned out to be a business scheme.

Suddenly, all these experiences had context. I hadn't been paranoid or oversensitive—I had been vulnerable and exploited, exactly as the neuropsychologist described.

My book details the specific strategies I developed for protecting myself from exploitation after diagnosis, including how to recognize red flags in relationships and when to walk away from situations that feel unsafe. These skills are essential for any late-diagnosed autistic adult.

4. Navigating Identity: "Why Couldn't I Be Normal?"

The Grief That Accompanies Relief

The diagnosis brought immediate relief—finally, an explanation for everything. But it also brought profound grief.

Sitting in that neuropsychologist's office with my mother, I felt the weight of a question I'd been asking my whole life: "Why couldn't I have been born normal?"

The Painful Questions That Surface

Why does it have to be so difficult? Watching peers navigate social situations effortlessly while you struggle with basic interactions is exhausting. Diagnosis confirms that this difficulty is permanent, not something you'll eventually outgrow.

Why did I have to live in a world where people don't understand? Autism doesn't just mean you're different—it means you're different in a world designed for neurotypical people. Every system, every social norm, every expectation assumes you process information the way the majority does.

Why me? This question isn't productive, but it's inevitable. Why do I have to work ten times harder for basic social competence? Why do I have to deal with sensory overload in normal environments? Why can't I just be like everyone else?

The Conflict Between Acceptance and Resentment

Diagnosis creates internal conflict:

Relief: Finally, I understand myself. Resentment: I have to live with this forever.

Validation: My struggles are real and have a name. Frustration: Knowing the cause doesn't make it easier.

Freedom: I can stop blaming myself. Pain: I have to accept limitations I didn't choose.

The Identity Shift

Before diagnosis, you might have thought: "I'm struggling, but I can fix this if I just try harder."

After diagnosis, the narrative changes: "I'm autistic. This is who I am. The world needs to accommodate me, not the other way around."

That shift from "I need to change" to "the world needs to change" is empowering but also frightening. It requires advocating for yourself in systems that don't want to accommodate you.

Simultaneous Freedom and Pain

The neuropsychologist's words—"Sonia has Asperger's Syndrome"—were simultaneously freeing and painful.

Freeing: I could stop pretending to be something I wasn't. I could seek accommodations without guilt. I could explain my needs without shame.

Painful: I had to grieve the "normal" life I'd never have. I had to accept that some things would always be harder for me. I had to come to terms with being different in a world that values conformity.

This duality is normal. You don't have to choose between relief and grief—you can feel both simultaneously.

5. What Depression Couldn't Explain

When One Diagnosis Isn't Enough

Before my autism diagnosis, I'd been diagnosed with depression. That label explained some things:

Low mood

Difficulty finding motivation

Social withdrawal

Negative self-talk

But depression didn't explain everything. There were symptoms and struggles that didn't fit neatly into a depression diagnosis.

The Gaps Depression Left

Sensory issues: Depression doesn't cause physical pain from clothing tags or inability to tolerate certain sounds. That's sensory processing differences associated with autism.

Social confusion: Depression can make you withdraw from social situations, but it doesn't explain the fundamental confusion about unwritten social rules and inability to read nonverbal cues.

Literal thinking: Missing sarcasm, taking things at face value, and struggling with abstract concepts aren't depression symptoms—they're autistic traits.

Need for routine: Depression can disrupt routines, but autism creates a neurological need for predictability and sameness that has nothing to do with mood.

Special interests: The intense focus on specific topics that brings joy isn't explained by depression—it's a core feature of autism.

Autism as the Missing Piece

The autism diagnosis filled in the gaps that depression left. It explained:

Why social situations were confusing, not just uncomfortable

Why sensory experiences could be physically painful

Why routines weren't just comforting but necessary

Why I thought differently than my peers in fundamental ways

Why certain behaviors that seemed immature were actually neurological differences

Depression Was Real, But It Wasn't the Whole Picture

Many autistic people are diagnosed with depression or anxiety first because mental health professionals are more familiar with those conditions. The underlying autism goes unrecognized, especially in girls and women who mask their autistic traits.

In my case, depression was real and valid. The years of bullying, social rejection, and feeling fundamentally broken had absolutely caused depression.

But the depression was secondary to the autism. I was depressed because I was an undiagnosed autistic person trying to survive in a neurotypical world without support or understanding.

The Relief of Complete Understanding

Having both diagnoses—depression and autism—finally provided a complete picture.

The autism explained the fundamental differences in how I processed the world.

The depression explained my emotional response to years of struggling with those differences without support.

Together, they gave me a roadmap for what I needed: autism-informed therapy, accommodations for my neurological differences, and treatment for the depression that resulted from years of struggling alone.

Moving Forward After Diagnosis

What Comes Next

Diagnosis isn't the end of the journey—it's the beginning of a new chapter. After those words "you're autistic," you face important decisions:

Who do you tell? Coming out as autistic to family, friends, employers, and educators is a personal choice with real consequences. Not everyone will understand or be supportive.

What accommodations do you need? In college, I could now request academic accommodations through disability services. In work settings, adults can request reasonable accommodations under the ADA.

How do you process the grief? The loss of the "normal" life you thought you'd have is real and deserves to be mourned. Therapy, support groups, and connecting with other autistic adults can help.

What strengths can you lean into? Autism isn't just deficits. Many autistic people have exceptional abilities in areas of interest, pattern recognition, attention to detail, and creative thinking.

Building Your Support System

After diagnosis, you need people who understand:

Other autistic adults who share your experiences

Therapists trained in autism (not just childhood autism)

Family and friends willing to learn and accommodate

Medical professionals who take your sensory needs seriously

Educators or employers who provide necessary supports

Reframing Your Past

Diagnosis allows you to look back at your life with new understanding:

Those "behavioral problems" in school? Autistic meltdowns from sensory overload.

That "immaturity" everyone criticized? Developmental delays that are part of autism.

Those "failed friendships"? Difficulty with unwritten social rules, not personal failings.

That "sensitivity"? Sensory processing differences and emotional intensity.

Reframing your past through an autistic lens reduces shame and increases self-compassion.

Embracing Your Autistic Identity

Over time, many late-diagnosed adults shift from viewing autism as a deficit to embracing it as identity. This doesn't mean denying real challenges—it means recognizing that autism is a fundamental part of who you are, not something to be cured or hidden.

This journey from diagnosis to acceptance isn't linear. You'll have days when you wish you were neurotypical and days when you appreciate your unique perspective. Both are valid.

Key Takeaways for Late-Diagnosed Adults

Your Diagnosis Is Valid

Whether you were diagnosed at 5, 19, or 55, your autism diagnosis is legitimate. Late diagnosis doesn't mean your autism is less real—it means it was overlooked or misunderstood for years.

Contradictory Emotions Are Normal

Feeling relief and grief simultaneously isn't confusing—it's completely normal. You can be grateful for understanding while also mourning the support you should have received years ago.

You're Not Alone

Thousands of adults are diagnosed with autism every year. The autistic community includes people diagnosed at every age, and late-diagnosed adults often have unique insights and experiences that help others.

Depression and Autism Often Co-Occur

If you have both diagnoses, you're not unusual. Many autistic people develop depression or anxiety from years of struggling without support. Treating both conditions is important for overall wellbeing.

Vulnerability Awareness Is Protective

Learning about your specific vulnerabilities—naivety, difficulty reading social situations, susceptibility to manipulation—isn't meant to scare you. It's meant to help you protect yourself going forward.

You Deserved Better

You deserved to be diagnosed earlier. You deserved accommodations and support. You deserved understanding instead of criticism. Acknowledging this isn't dwelling on the past—it's validating your experience.

The Future Can Be Different

With diagnosis comes access to:

Appropriate therapeutic support

Accommodations in education and employment

Community with other autistic people

Self-understanding that reduces shame

Strategies tailored to your specific needs

Your past may have been filled with confusion and struggle, but your future can include acceptance, support, and thriving as your authentic autistic self.

Ready to explore the complete journey from diagnosis through self-acceptance? My book provides the full story of receiving an autism diagnosis in college and learning to navigate the world as an openly autistic adult.

Final Thoughts

Walking out of that neuropsychologist's office with my autism diagnosis, I carried a complex mix of emotions that would take years to fully process. The relief of finally understanding myself. The grief of all the years I'd struggled without support. The fear of future vulnerabilities. The hope that maybe, finally, things could be different.

If you're reading this as a newly diagnosed adult or someone considering evaluation, know that these feelings are valid and shared by countless others who've walked this path.

Diagnosis doesn't fix everything—but it gives you the framework to understand everything. And that understanding, painful as it sometimes is, is the foundation for building a life that works with your neurology instead of against it.

The blindfold is off. The maze is still there, but now you can see it clearly. And seeing it clearly is the first step toward finding your way through.

For the complete story of life before, during, and after autism diagnosis—including practical strategies for navigating college, relationships, and self-advocacy as an autistic adult—get my book today.

A Parent's Guide to Supporting Neurodiverse Children