The Double Isolation of Being Neurodivergent and Different

Table of Content

Intro

Watched Like a Prisoner: When School Restrictions Follow You Everywhere

When Your Therapist Becomes Another Source of Shame

Happy Diwali: Your Place Is on the Floor in the Corner

The Big Blow-Up: When Rejection Becomes Confrontation

The Lessons That Emerged From Isolation

From Corner Floors to Claiming Space

The Double Isolation of Being Neurodivergent and Different

Imagine sitting alone on a gymnasium floor during a cultural celebration meant to bring your community together. While everyone around you laughs, dances, and connects with their families, you're relegated to a corner—not by choice, but because no one wants you there. Not even the people who share your heritage, your language, your traditions.

This wasn't a one-time incident in my life. It was a pattern that repeated itself at Indian-American gatherings throughout my adolescence, adding another painful layer to the isolation I already experienced at school. When you're neurodivergent, the rejection from peers is crushing. But when your own cultural community—the place where you're supposed to find belonging—also turns you away, the loneliness becomes unbearable.

The question that haunted me during those years was simple yet devastating: If I'm not welcomed here, then where? Where do I belong when I'm too different for my school and too "problematic" for my community?

This is the story of navigating restrictions, cultural backlash, and the profound isolation that comes when rejection follows you everywhere—even to places meant to celebrate who you are.

Watched Like a Prisoner: When School Restrictions Follow You Everywhere

The consequences of being labeled a "problem child" didn't stay confined to classroom walls. By sixth grade, the restrictions extended to every school-related activity, including something as simple as a band concert.

I was part of the school band, and performing at the Winter Holiday Concert in the high school auditorium was mandatory. But Ms. Anderson pulled me and a group of popular girls out of class before the concert with specific instructions.

"I need you all to watch Sonia at this upcoming band concert," she announced. "At the last band concert, parents complained that she was a distraction and disrespectful. We can't afford to have that happen again."

I had to be watched at a band concert. Like a prisoner awaiting a court hearing, I needed constant supervision just to sit and listen to music. The girls assigned to monitor me were from the popular group—the only ones who gave me any attention, though it was never sincere.

I later discovered from a therapist that parents had instructed their children to stay away from me. These complaints to the school weren't about my behavior at the concert—they were about preventing me from participating at all. Families wanted me gone, and they used any excuse to make it happen.

The Breaking Point

During the concert, while sitting and listening to other bands perform, the weight of it all crashed down on me. Everyone else had friends. Everyone else belonged. I was alone and embarrassed, constantly monitored as if I might explode at any moment.

I broke down in tears.

Looking back, the school should have offered me an alternative: give me an A for the semester in exchange for not performing. It would have saved me the humiliation and relieved other students from the burden of playing "watch guard." Creating exceptions to mandatory rules for neurodivergent students isn't weakness—it's compassion and common sense.

The isolation experienced at school was only one part of the story. The cultural rejection that followed created wounds that cut even deeper. Discover the complete journey of navigating dual rejection and finding your voice in the full book.

When Your Therapist Becomes Another Source of Shame

You'd expect a therapist to provide a safe space—somewhere you can express yourself without judgment. Instead, Dr. Patel, a therapist who shared my Indian cultural background, became another voice of shame.

Every session felt like being scolded by a disapproving parent rather than receiving professional mental health support. He repeatedly reminded me how he had advocated to keep me at Forest Ridge School District, as if I should be perpetually grateful and guilty.

"When I went to your school, they wanted to throw you out that day," he'd say. "If I hadn't been there to advocate for you, that would've been the end of it."

This wasn't helpful. I didn't learn emotional regulation, conflict resolution, or social skills. The only thing keeping me at school was fear of my parents' wrath if I got expelled and transferred.

The Question Without an Answer

Dr. Patel did ask one question worth pondering: "If you don't respect yourself, how do you expect others to respect you?"

It was a valid concept—but completely meaningless without guidance on how to achieve self-respect. For someone who had been bullied, rejected, and constantly told they were the problem, self-respect wasn't something I could just decide to have. It needed to be taught through self-esteem-building exercises and therapeutic support.

Instead, I received lectures about gratitude and behavior modification, delivered in a manner resembling disappointed Indian parents rather than an objective mental health professional.

Critical lesson for mental health professionals: Individuals who have faced peer rejection and bullying typically have low self-esteem. If you're going to emphasize the importance of self-respect, you must provide concrete direction on how to build it. Otherwise, you're just adding another voice to the chorus telling them they're not good enough.

Professional support should heal, not harm. Learn how to find the right therapeutic help and what effective intervention actually looks like in the complete book.

Happy Diwali: Your Place Is on the Floor in the Corner

My parents were members of an Indian-American Physicians Group, composed mainly of families from Forest Ridge and surrounding towns. Many attendees were classmates and their families—people who already gave me the cold shoulder at school.

At a previous event held in the Forest Ridge Middle School gymnasium, I tried sitting with classmates Amisha and Beena. Amisha gave me a death stare that I didn't pick up on at the time. Beena kept her answers short, trying to be polite without causing drama. Once Amisha got up, Beena immediately followed.

Another classmate, Leena, kept her distance entirely. I understood why—they were weirded out by my eccentric behaviors. But understanding didn't make it hurt less.

The Diwali Gathering That Changed Everything

The next gathering was a Diwali celebration at a community center about thirty minutes from Forest Ridge. My mom was out of town visiting my brother Jay at college, leaving me with my dad for the weekend. I knew he wouldn't let me skip the event, especially because our close family friends, the Ahujas, were supposed to attend.

I felt particularly close to the Ahuja daughters, especially Priyanka, who battled her own mental health challenges. Knowing she'd be there gave me comfort, though anxiety gnawed at me all day.

I went to the hairdresser earlier, getting nice curls put in my hair, hoping it would help me feel more confident. My dad assured me multiple times that the Ahujas were coming. But when we arrived, Priyanka's parents informed me she wasn't there.

I tried saying hi to people—classmates from school and their friends from neighboring towns. They barely acknowledged me, treating me as invisible.

So I sat on the floor in a corner of the hallway. Alone.

I understand now why they didn't want me around—rumors had spread, and my acting out at school had weirded everyone out. In all fairness, they were behaving like most of my peers, embarrassed and ashamed to be associated with me.

But it hit differently coming from my own cultural community. At school, I was different because I was Indian, neurodivergent, and didn't fit in. At Indian gatherings, I was rejected despite sharing heritage, language, and traditions with everyone there.

If I wasn't welcomed here, then where? Where could I possibly find acceptance?

The bitter truth: there was nowhere left to go.

A Small Act of Kindness

I sat in that corner for what felt like hours, staring at the outdated floor tiles—white with sprinkles of light blue, desperately needing remodeling. My dad was too busy socializing with friends to check on me. People occasionally glanced over, shooting me looks, but I kept my eyes down.

Only one girl approached me. Nidhi, whom I'd met years earlier at a family friend's gathering, walked over with genuine concern.

"Sonia, people are feeling sorry for you because you're by yourself," she said.

"They hate me, Nidhi."

"But I don't hate you. Why do they hate you?" she asked sympathetically.

I explained briefly about everything at school. She listened, expressed sympathy, and eventually had to leave. Before she went, she made sure to tell me she didn't hate me.

That small acknowledgment meant everything.

But here's the truth: If people really felt sorry for me, they could have easily invited me to join them. It's that simple. Instead, their "pity" was just another form of rejection, dressed up in more socially acceptable language.

Sitting on that floor was just the beginning. I'd be coerced to attend many more Indian events where I was left to fend for myself. Eventually, I graduated from sitting on floors to sitting at tables—alone. My only source of comfort was that chairs felt better than floors screaming "Please remodel me."

Cultural rejection adds a unique dimension to the isolation faced by neurodivergent individuals. The journey from floor corners to finding genuine community is transformative. Read the complete story to understand how identity, belonging, and acceptance intersect.

The Big Blow-Up: When Rejection Becomes Confrontation

After the floor incident, my anxiety about attending Indian gatherings intensified. I felt it in my gut—I didn't fit in, and everyone knew it.

Another gathering came in spring 1995. My whole family and a cousin were attending, which meant I couldn't avoid it. As soon as we arrived, I spotted Amisha and Beena sitting at a table. I told my mom people from school were there.

Despite knowing how they'd treated me before, my mom thought it was important I try to make friends. She approached their table and asked if I could sit with them. They were polite to her face and agreed.

Once my mom left to sit with my dad and their friends, everything changed.

I was sitting next to a friend of Amisha and Beena's—someone from a different school who I didn't know well. I tried joining their conversation, but I didn't have the skills to smoothly insert myself into an ongoing discussion. Understandably, their friend got annoyed and made a snarky remark.

A full argument erupted. Amisha and Beena laughed at their friend's comments, half-heartedly saying "Stop, stop" while clearly supporting her.

"I'm trying to have a conversation with MY friends. Who are you?" their friend asked snarkily.

"I was just trying to be friendly and join the conversation," I replied timidly.

"You're really annoying. Leave us alone."

"How am I the one being annoying?"

"The way you're acting. You won't even let us talk. Are you always this annoying?"

"I'm not annoying."

"Sonia, you weren't even invited to sit here. Your mom had to come and ask."

"So?"

"My point exactly. Why don't you name your friends or count how many you have? I bet you don't have many."

That cut deep. She was right—I didn't have many friends. But I responded defiantly, "I do. In fact, I'm throwing a huge birthday party for when I turn 13."

"I bet nobody will even show up."

That was enough. I left the table as Amisha, Beena, and their friend shot me dirty glares. I heard laughter as I walked away.

The Aftermath

I ran into Nisha, a friend from my second-grade redo year, who happened to be at the gathering. I told her what happened. She mentioned thinking Amisha, Beena, and their friend were really nice, then went to hear their version of events.

Years later, I learned those girls called me a "bitch" behind my back. In my mind, that was actually an improvement—I'd rather be called a bitch than a baby.

The patterns of rejection, confrontation, and resilience shape who we become. Understanding these dynamics and learning how to navigate them changes everything. Explore the full journey and the strategies that finally worked in the complete book.

The Lessons That Emerged From Isolation

Looking back at those painful experiences—being monitored at band concerts, sitting alone on gymnasium floors, enduring confrontations at cultural gatherings—several critical lessons emerge:

For Mental Health Professionals

Create genuine safe spaces. Reinforcing how much you had to advocate for a client each session comes across as shaming, not supportive. Focus on emotional regulation, conflict resolution, and social skills development.

Provide direction, not just concepts. Telling someone with low self-esteem to "respect themselves" without teaching them how is useless. Build concrete strategies for developing self-worth through exercises and consistent support.

Maintain professional boundaries. Shared cultural background shouldn't blur the lines between therapist and family member. Objective, professional care is essential regardless of cultural connections.

For Parents and Community Leaders

Isolation compounds trauma. When a child is already struggling socially at school, adding rejection from their cultural community creates unbearable loneliness. One safe space—just one—can make all the difference.

Teach children compassion. If you notice a child sitting alone at community gatherings, teach your children to include them. Model the kindness you want to see. Small gestures of acceptance can have profound impacts.

Question the narrative. When parents tell their children to avoid someone, ask why. Often, the reasons stem from fear and misunderstanding rather than legitimate concerns. Challenge the impulse to ostracize neurodivergent community members.

For Those Experiencing Similar Rejection

Your worth isn't determined by acceptance. The communities that reject you aren't equipped to see your value—that's their limitation, not your deficiency.

Find your people. They exist, even when it feels impossible. Sometimes you have to look beyond traditional spaces to find genuine belonging.

Document your journey. One day, your story of surviving dual rejection will help someone else feeling that same crushing isolation.

From Corner Floors to Claiming Space

The girl who sat on that gymnasium floor, staring at outdated tiles while cultural celebrations happened around her, eventually learned something powerful: belonging isn't about forcing yourself into spaces that don't want you. It's about finding or creating spaces where your authentic self is welcomed.

The journey from being monitored at band concerts to advocating for neurodivergent acceptance wasn't linear. It required navigating therapists who shamed rather than healed, enduring cultural gatherings where loneliness felt suffocating, and confronting the painful reality that sometimes your own community can be your harshest critics.

But here's what those difficult years taught me: The restrictions placed on you don't define your worth. The people who reject you don't determine your value. And the isolation you feel today doesn't predict the community you'll find tomorrow.

The question "If I'm not welcomed here, then where?" eventually found its answer—not in the spaces that rejected me, but in the understanding that I could create my own belonging.

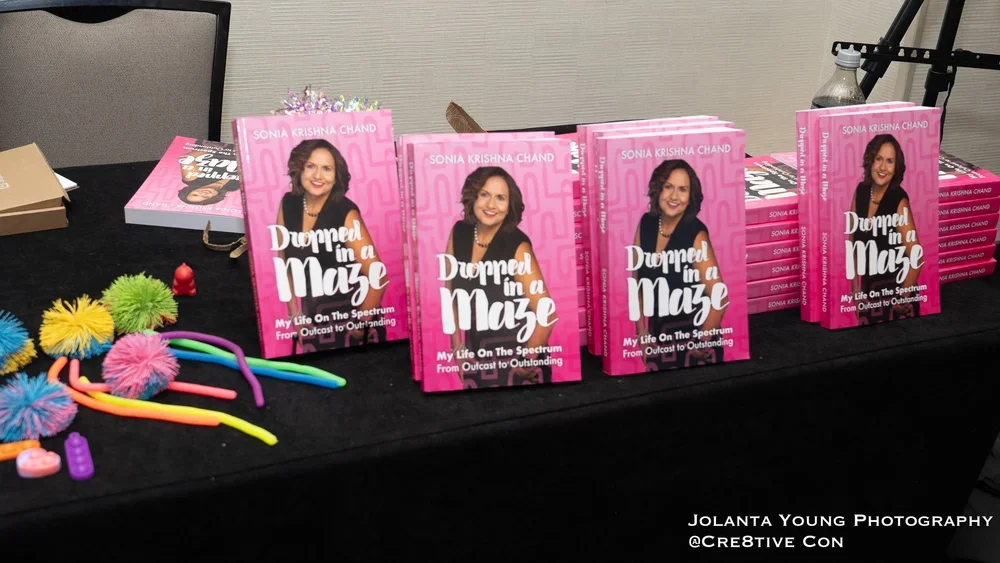

This is just one chapter in a longer story of navigating neurodivergence, cultural identity, and finding your voice when everyone tells you to be quiet. For the complete journey—including how professional support evolved, what finally broke the cycle of isolation, and how advocacy transforms pain into purpose, read the full book and discover that your differences are your greatest strengths.